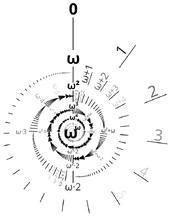

Visualization of ordinals up to \(\omega^\omega\) as iterated hierarchies

- Not to be confused with the linguistic definition (meaning words such as "first", "second", "third" etc.).

In set theory, an ordinal number, or simply ordinal, is an equivalence class of well-ordered sets under the relation of order isomorphism. Intuitively speaking, the ordinals form a number system that can be viewed as an extension of the natural numbers into infinite values. They are important to googology since they describe the growth rates of functions via the fast-growing hierarchy and other ordinal hierarchies, as well as their appearances in other meeting points between googology and set theory.

The class of ordinals is denoted \(\mathrm{On}\) or \(\mathrm{Ord}\). This is a proper class.

Definition[]

Here we will describe a few formal and informal ways to introduce the ordinal number system.

As an extension of the natural numbers[]

It is easiest to think intuitively of the ordinals as an extension of the nonnegative integers. The nonnegative integers are 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ..., but the ordinal system extends this with the first transfinite ordinal \(\omega\). \(\omega\) is the first ordinal larger than all the natural numbers.

Next we can continue with the ordinal \(\omega + 1\). Strangely, the definition of ordinal addition tells us that this is different from \(1 + \omega\), which is simply equal to \(\omega\). \(\omega + 1\), however, is larger than \(\omega\). Naturally there are further ordinals such as \(\omega + 2\), \(\omega + 3\), etc. and eventually we reach \(\omega + \omega\).

The number of ways to add n ordinals is given by the sequence 1, 2, 5, 13, 33, 81, 193, 449, … (OEIS A005348).

\(\omega + \omega\) can also be written \(\omega \times 2\). Oddly enough, \(2 \times \omega = \omega\) (this is explained in the section below on small transfinite ordinals). Then come \(\omega \times 3\), \(\omega \times 4\), \(\omega \times 5\), and so forth until we reach \(\omega \times \omega = \omega^2\), followed by \(\omega^3\), \(\omega^4\), ..., \(\omega^\omega\), \(\omega^{\omega + 1}\), \(\omega^{\omega^\omega}\), \(\omega^{\omega^{\omega^\omega}}\), ...

It is very important not to forget that the many intermediate ordinals, like \(\omega^{\omega^{\omega2+1}+\omega}+\omega^{\omega^5+\omega^4\times 6+\omega^2}+427\), still get counted here, and aren't missed out.

Order type[]

Order types are the most general way to define ordinals. Under this definition, an ordinal is an equivalence class of well-ordered sets under the relation of order isomorphism.

A binary relation \(\leq\) is a well-ordering of the set \(S\) iff all the following are true for all \(a,b,c\) in \(S\):

- \(a \leq b \vee b \leq a\)

- \(a \leq b \wedge b \leq c \Rightarrow a \leq c\)

- \(a \leq b \wedge b \leq a \Rightarrow a = b\)

- Every subset of \(S\) has a minimum element.

A well-ordered set (or woset) a consists of a set \(S\) and a relation \(\leq_S\) that is a well-ordering of \(S\).

An order isomorphism between two wosets \((S, \leq_S)\) and \((T, \leq_T)\) is a bijection \(f : S \mapsto T\) such that \(\forall x,y \in S : x \leq_S y \Leftrightarrow f(x) \leq_T f(y)\). We say that two orders are order isomorphic if there exists an order isomorphism between them. It is not difficult to show that relation of being order isomorphic is an equivalence relation, and thus partitions all well-ordered sets into equivalence classes, which we will call order types. Each order type is represented by a distinct ordinal.

All empty wosets are mutually order isomorphic, and two wosets with different cardinalities cannot be order isomorphic, so it follows that the empty wosets form an order type. We will label this class "0". With more difficulty, it can be shown that for all finite cardinals n, the wosets with cardinality n form an order type which we call n. So already we have the ordinals 0, 1, 2, 3, ...

The order type of a woset with a greatest element is called a successor ordinal. Ordinals that are not successor ordinals or 0 are called limit ordinals. For every ordinal \(\alpha\), there is a minimal successor ordinal \(\beta > \alpha\) which we call the successor to \(\alpha\), denoted \(\alpha + 1\).

Von Neumann definition[]

The von Neumann definition gives us a specific way to define ordinals within the framework of set theory. It is handy as it can represent ordinals as actual objects within a set theory. Under the von Neumann definition, an ordinal number is defined as the set of all smaller ordinals, or formally a transitive set well-ordered by \(\in\).

Whereas the above definition is indisputable, this particular definition is not always applicable and it is a good idea to clarify when it is being used. It is convenient since it lets us easily apply set descriptors to ordinals with no explanation needed at all: recursive ordinal, countable ordinal, etc.

Introduction[]

An ordinal number is defined as the set of all smaller ordinal numbers. Formally, an ordinal \(\alpha\) is \(\{\beta: \beta < \alpha\}\), and the successor to an ordinal is defined as \(\alpha + 1 = \alpha \cup \{\alpha\}\).

We start with \(0 := \{\}\); zero is the empty set, since no ordinal number is smaller than zero. We continue with \(1 := \{0\} = \{\{\}\}\), \(2 := \{0, 1\} = \{\{\}, \{\{\}\}\}\), \(3 := \{0, 1, 2\} = \{\{\}, \{\{\}\}, \{\{\}, \{\{\}\}\}\}\), etc.

Small transfinite ordinals[]

The next ordinal after all these is \(\{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\}\), the set of all nonnegative integers. We represent this with the Greek letter \(\omega\) (omega), the least transfinite ordinal. Next, we can define \(\omega + 1 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots, \omega\}\), \(\omega + 2 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots, \omega, \omega + 1\}\), etc.

The specifics of ordinal addition are not detailed here, but the general idea should be fairly clear from these examples. It is important to note that addition on the ordinals is often not commutative. \(\omega + 1 > \omega\), but \(1 + \omega = \omega\). Similarly, \(\omega + \omega = \omega \times 2\) does not equal \(2 \times \omega \) = 2 + 2 + 2... (with ω 2's) = \(\omega\).

The supremum of all the \(\omega + n\) is \(\{0, 1, 2, \ldots, \omega, \omega + 1, \omega + 2, \ldots\} = \omega + \omega = \omega \times 2\). Next we have the series \(\omega + \omega + \omega = \omega \times 3, \omega \times 4, \omega \times 5, \omega \times 6, \ldots, \omega \times \omega = \omega^2, \omega^3, \omega^4, \ldots, \omega^\omega, \omega^{\omega^\omega} = {}^3\omega, \omega^{\omega^{\omega^\omega}} = {}^4\omega, \ldots\)

Eventually we reach \(^\omega\omega = \omega^{\omega^{\omega^{.^{.^.}}}}\), famously known as \(\varepsilon_0\) (epsilon-zero). (To googologists, the exponentiation might seem like a fairly arbitrary choice, but in fact it is not — it is important in induction proofs, for example, and also a sensible starting point for the Veblen hierarchy, as seen below.) \(\varepsilon_0\) is a fixed point such that \(\varepsilon_0 = \omega^{\varepsilon_0}\); \(\varepsilon_1\) can be defined as fixed point: \(\varepsilon_1 = \varepsilon_0^{\varepsilon_1}\). In general, \(\varepsilon_{\alpha+1}\) is a fixed point for \(\varepsilon_{\alpha+1} = \varepsilon_{\alpha}^{\varepsilon_{\alpha+1}}\). Examples of "epsilon numbers" are \(\varepsilon_0, \varepsilon_1, \varepsilon_2, \varepsilon_3, \varepsilon_\omega, \varepsilon_{\varepsilon_0} \ldots\).

The limit of the hierarchy of \(\varepsilon_\alpha\) leads us to \(\varepsilon_{\varepsilon_{\varepsilon_{._{._.}}}}\), sometimes called \(\zeta_0\). The "zeta numbers" are the solutions to the equation \(\zeta = \varepsilon_\zeta\). We could extend this to another letter, like \(\eta\), using \(\zeta_{\zeta_{\zeta_{._{._.}}}}\) but we only have finitely many Greek letters, so we need a new way to generalise.

Veblen hierarchy[]

We only have finitely many Greek letters, so the next step is to generalize these. Define the Veblen hierarchy as \(\varphi_0(\alpha) = \omega^\alpha\), and define \(\varphi_{\beta + 1}(\alpha)\) as the \(\alpha\)th (counting from \(0\)) solution \(\gamma\) to the equation \(\varphi_\beta(\gamma) = \gamma\). This gives us \(\varphi_1(\alpha) = \varepsilon_\alpha, \varphi_2(\alpha) = \zeta_\alpha, \varphi_3(\alpha) = \eta_\alpha, \ldots\). Further we can define \(\varphi_\alpha\) for any transfinite ordinal, using a different case for limit \(\alpha\).

The limit of the Veblen hierarchy is \(\varphi_{\varphi_{\varphi_{._{._..}.}(0)}(0)}(0) = \Gamma_0\), the Feferman–Schütte ordinal. It is the smallest solution to the equation \(\varphi_{\Gamma_0}(0) = \Gamma_0\).

Past Veblen hierarchy[]

There are many different ways to write ordinals past the limit of the Veblen hierarchy.

Extended Veblen function[]

- Main article: Veblen_function#The extended (finitary) Veblen function

This is an extension of the Veblen function to a finite number of arguments.

Let z be an empty string or a string with one or more zeros \(0,0,...,0\) and s be an empty string or an arbitrary string of ordinal variables \(\alpha_1, \alpha_2,...,\alpha_n\) with \(\alpha_1>0\). The binary function \(\varphi(\alpha, \gamma)\) can be written as \(\varphi(s,\alpha, z,\gamma)\) where both s and z are empty strings.

The extended Veblen functions are defined as follows:[1]

- \(\varphi(\gamma)=\omega^\gamma\),

- \(\varphi(z,s,\gamma)=\varphi(s,\gamma)\),

- if \(\alpha_{n+1}>0\), where \(n\geq 0\), then \(\varphi(s,\alpha_{n+1}, z, \gamma)\) denotes the \(1+\gamma\)th common fixed point of the functions \(\xi \mapsto \varphi(s, \beta, \xi,z)\) for each \(\beta<\alpha_{n+1}\).

Ordinal collapsing functions[]

- Main article: Ordinal collapsing function

These are functions that use larger ordinals (usually either uncountable or admissible) to create smaller ordinals. An example is Buchholz's function.

Ordinal notations[]

- Main article: Ordinal notation

Ordinal notations, such as Taranovsky's Ordinal Notation and Rathjen's ordinal notations, are usually created using a recursive set of terms formulated as strings or arrays (often called \(T\) or \(OT\)) written using a countable set of alphabets, and a recursive well-ordering on terms (often called \(<\)). In particular, terms of ordinal notations are not necessarily ordinals, but by the well-foundedness of the total ordering, they essentially describe recursive ordinals, because the order type of a term in a well-ordered set is an ordinal.

Beginners should be very careful that many of people in this community misunderstand the notion of ordinal notations, and there are many wrong information given by them. If they define their own notations of ordinals and call the notations "ordinal notations" without showing explicit algorithms to compute the recursive set of terms and the recursive well-ordering, then it is reasonable to guess that they misunderstand the definition of the notion of an ordinal notation.

References[]

- ↑ Maksudov, Denis. Fundamental sequences for extended Veblen function. Traveling To The Infinity. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

External links[]

- ordCalc - an ordinal calculator

- An interactive diagram for ordinals up to \(\varepsilon_{\varepsilon_0}\)

Basics: cardinal numbers · ordinal numbers · limit ordinals · fundamental sequence · normal form · transfinite induction · ordinal notation · Absolute infinity

Theories: Robinson arithmetic · Presburger arithmetic · Peano arithmetic · KP · second-order arithmetic · ZFC

Model Theoretic Concepts: structure · elementary embedding

Countable ordinals: \(\omega\) · \(\varepsilon_0\) · \(\zeta_0\) · \(\eta_0\) · \(\Gamma_0\) (Feferman–Schütte ordinal) · \(\varphi(1,0,0,0)\) (Ackermann ordinal) · \(\psi_0(\Omega^{\Omega^\omega})\) (small Veblen ordinal) · \(\psi_0(\Omega^{\Omega^\Omega})\) (large Veblen ordinal) · \(\psi_0(\varepsilon_{\Omega + 1}) = \psi_0(\Omega_2)\) (Bachmann-Howard ordinal) · \(\psi_0(\Omega_\omega)\) with respect to Buchholz's ψ · \(\psi_0(\varepsilon_{\Omega_\omega + 1})\) (Takeuti-Feferman-Buchholz ordinal) · \(\psi_0(\Omega_{\Omega_{\cdot_{\cdot_{\cdot}}}})\) (countable limit of Extended Buchholz's function) · \(\omega_1^\mathfrak{Ch}\) (Omega one of chess) · \(\omega_1^{\text{CK}}\) (Church-Kleene ordinal) · \(\omega_\alpha^\text{CK}\) (admissible ordinal) · recursively inaccessible ordinal · recursively Mahlo ordinal · reflecting ordinal · stable ordinal · \(\lambda,\gamma,\zeta,\Sigma\) (Infinite time Turing machine ordinals) · gap ordinal · List of countable ordinals

Ordinal hierarchies: Fast-growing hierarchy · Hardy hierarchy · Slow-growing hierarchy · Middle-growing hierarchy · N-growing hierarchy

Ordinal functions: enumeration · normal function · derivative · Veblen function · ordinal collapsing function · Weak Buchholz's function · Bachmann's function · Madore's function · Feferman's theta function · Buchholz's function · Extended Weak Buchholz's function · Extended Buchholz's function · Jäger-Buchholz function · Jäger's function · Rathjen's psi function · Rathjen's Psi function · Stegert's Psi function · Arai's psi function

Uncountable cardinals: \(\omega_1\) · omega fixed point · inaccessible cardinal \(I\) · Mahlo cardinal \(M\) · weakly compact cardinal \(K\) · indescribable cardinal · rank-into-rank cardinal

Classes: \(\textrm{Card}\) · \(\textrm{On}\) · \(V\) · \(L\) · \(\textrm{Lim}\) · \(\textrm{AP}\) · Class (set theory)

Concepts: googology · large number · eventual domination · ordinal · cardinal · recursion · infinity

Important numbers and functions: googol · googolplex · -illions · hyper operators · Graham's number · Extensible-E System · Bowers' Exploding Array Function · Bird's array notation · TREE sequence · Busy beaver function · fast-growing hierarchy · Rayo's number

People: Chris Bird · Jonathan Bowers · Harvey Friedman · Lawrence Hollom · André Joyce · Leo Moser · Robert Munafo · Sbiis Saibian · Aarex Tiaokhiao